Transformational Music Theory: A Mathematical Approach To Analyzing Music

Combining group theory and music theory. | July 22, 2024

Table of Contents

Prerequisites

This post uses group theory and set theory, so familiarizing yourself with those fields is encouraged before reading this piece. Additionally, I try to explain some basic music theory, but prior knowledge of western music theory will help tremendously in understanding this. This video seems to cover most of what you need to know.

Introduction

In the late 19th century, composers of the romantic era began to play around with a new type of sound, one astray from the common sound of the Western musical world. The composers took the dull blues and greens of the Western classical palette and added a bright kermes red, deep tyrian purple, and a glaucous blueish-green. They did this through the use of chromaticism and atonality.

Atonality is music which has no tonal center, i.e. atonal music sounds much different than music we might be used to. For example, take Schoenberg's 3 Klavierstücke, Op. 11: No. 1, Mäßige Viertel. Chromaticism sounds more familiar, and keeps a tonal center, but will use notes outside the key (see Debussy's Prélude à l'aprés-midi d'un Faune) Both forms of composition, however, are used by composers to stray from the techniques of tonal music and tonality1.

This is an example of tonality. Tonal music is music that is built off of some type of scale, which will imply a tonal center. The two most common ones are the major and minor scales. Using these scales, we can build chords using only the notes in the scale, such as those above. Using the notes of the scale helps keep our tonal center (the first note of the scale, or the root), and thus we are able to create feelings of tension by venturing away from the root and release by returning.

By venturing farther away from tonality, the Late Romantic-era composers created music in which conventional methods of analysis could not work. This led to the creation of transformational theory, which instead of looking at musical objects in relation to the tonic, it viewed them in relation to each other. Instead of thinking of a \(I-V\) cadence (the first two chords from the snippet above), we think of a "Dominant operation". We look at the chords in context of the surrounding musical objects, i.e. we care less about the content of the chord itself and more about how we got to the chord and how we leave it.

Basic Music Theory

Anyone who has taken an introductory music theory course, or studied music theory at some point, should be able to skip this section.

To get to transformational theory and the math behind it, it's important to understand some of the basics. Western music is built off of the 12 tone equal tempered tuning system, meaning the following twelve notes are the only notes available:

Of those twelve notes, we construct a 7-note scale called the major scale, which is the most common scale in Western classical music. Our major scale is as follows:

We can create modes of this scale by altering which note we start on. Starting on C as above gives us a major scale, but if we start on the 6th degree, A, we get an A minor scale.

The nice thing about 12 TET is that we can transpose these scales, and they still sound nice. So if we raise all the notes in the diatonic scale by a half step (one note chromatically), we get a new scale. Since this one starts on Db, we'll call it the Db major scale, and we'll have Bb minor if we start on the 6th degree, as before.

Now that we have a scale, we can create chords. As we will see, chords are very important in transformational theory, as they are in most forms of analysis. Let's recall the \(I-V-I\) cadence from the beginning.

The \(I\) chord is built from the first, third, and fifth notes. The \(V\) chord is built from the fifth, seventh, and second notes (we wrap around the scale once we reach the end). Similar to how we built those chords, we can build any other 3 note chord by using every other note. We call the intervals these chords are built from "thirds", and we call the chord a "triad". The triad is built off of the "root", and the second and third notes are called the third and fifth, respectively.

These triads contain two types of thirds: a major third, which has 3 notes in between, and a minor third, which has 2 notes in between. For example, D and F form a minor third because D# and E are in between them in the chromatic scale, while C and E form a major third because C#, D, and D# are in between the two.

Most of musical analysis before Transformational Theory (e.g. Schenkerian analysis), focused on relationships between these chords and the scale degrees they are built off of. For example, we could look at a piece and find the chords at different points. We can analyze why the piece might make us feel a certain way by looking at its motion harmonically, i.e. how it moves from chord to chord. Let's analyze the following progression as an example.

If we wanted to understand why our progression feels so resolved, we can analyze this using everything we've learned so far. We end on a \(I\) chord, meaning that the last chord is built off of the tonal center, or tonic, of the scale/key. Understandably, other chords in this key will feel unresolved, but the final chord does not need to resolve- it is the resolution. We can also take this a step further, noting that the final two chords form a \(V-I\) cadence, commonly known as an authentic cadence. The authentic cadence is perhaps the most common sequence of chords in any form of western music. This is because the \(V\) chord has a lot of tension, and the \(I\) chord resolves all of the tension.

There are more tools we can use to analyze this progression, but really, what we've covered so far is all you need to understand the music theory below.

Transformational Theory

Now that we have a basic grasp of conventional analysis, we can start to look at transformational theory and its math.

Transformational theory ignores the key we're in and chord we're on. It works by analyzing the relationship between any two chords rather than the chords themselves. As David Lewin writes in Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations (the foundational text of transformational theory), transformation theory asks "If I am at s and wish to get to t, what characteristic gesture should I perform in order to arrive there?" (159).

Let's take a look at an example. Say we see the following progression in a piece of music:

"Functionally," (i.e. analyzing the chords in relation to the key) we'd analyze this as a \(I-iii\) progression. But, let's look at the transformation that is taking place. We are changing one note and moving it down a half step: C moves down to B. In some forms of transformational theory, this is called a leading tone exchange.

The obvious question is: how can we rigorously define these transformations? Before we get to defining these transformations for chords, let's think of transformations we can perform with the notes of the chromatic scale. For instance, we could have a transformation that makes a key go up by 6 notes. Let's call it \(T_{6}\). We could have this transformation for any \(n\) keys, so we can define the operation \(T_{n}\) to represent moving $n$ keys up the chromatic scale.

What are some properties of this transformation? We know:

- We have a function $T_0$ that acts as if we never applied the function. $$T_0(k) = k$$

- Applying $T_n$ and then $T_{-n}$ gives us the value we started with.

- $T_{p}+(T_{q}+T_{r}) = (T_{p}+T_{q})+T_{r}$

So we have an identity element, an inverse, and associativity: we have a group! Our group is isomorphic to the group $\mathbb{Z}_{12}$, or the cyclic group with 12 elements (0-11). We can use this to our advantage, and represent our group as numbers instead of note names. This helps us abstract away the irrelevant details like which key we are in, and focus on the transformations that we are applying. A common way of representing our group of notes is through a clock diagram like below (we'll use this to help visualize transformations later on):

Now that we can define these transformations for a single note, let's see how we can generalize this to apply to any transformation on an object. Lewin did this by defining a generalized interval system (GIS). He defines it as follows:

A Generalized Interval System (GIS) is an ordered triple $(S, \text{IVLS}, \text{int})$, where S, the space of the GIS, is a family of elements, $\text{IVLS}$, the group of intervals for the GIS, is a mathematical group, and $\text{int}$ is a function mapping $S \times S$ into $\text{IVLS}$, all subject to the two conditions (A) and (B) following.

$\quad$(A): For all $r$, $s$, and $t$ in $S$, $\text{int}(r, s) \circ \text{int}(s, t) = \text{int}(r, t)$.

$\quad$(B): For every $s$ in $S$ and every $i$ in $\text{IVLS}$, there is a unique $t$ in $S$ which lies [in] the interval $i$ from $s$, that is a unique $t$ which satisfies the equation $\text{int}(s, t) = i$ (Lewin, 1987, p. 26)

In simpler terms, a GIS contains a given musical space (e.g. a chromatic or diatonic scale), a group of intervals (this could be $\mathbb{Z}_{12}$ or something similar), and a function (which we call the interval function $\text{int}$) which maps our Cartesian Product $S \times S$ to the group of intervals.

The conditions Lewin sets are very useful as they make our group into a G-torsor, but if you have no idea what that is, don't worry, we won't need to deal with that for today.

Now that we have a basic understanding of what a GIS is, we can look at some examples. Let's consider a basic tonal example: our musical space shall be the C major scale. We'll then define the function $\text{int} : S \times S \to \mathbb{Z}_{7}$ such that $\text{int}(s,t)$ is the minimum number of scale steps going up from $s$ required to reach $t$. For example, we have $\text{int}(C, D) = 1$ and $\text{int}(C, G)=4$, while $\text{int}(F, D)=5$, not $-2$. It's easy to find our identity ($int(a, a)$) and inverse elements ($int(a, b) + int(b, a)$).

Neo-Riemannian Analysis

So far, we've done a lot of abstract math/music theory with very little application. We know that we can model intervals as functions which can form groups, we have a very rigorous way to define these groups, but absolutely no idea how to apply it. For this, music theorists have created several branches of transformational theory, but for today, we'll use Neo-Riemannian Analysis. It's primarily used in analyzing triadic music, tonal or atonal.

Considering most of the people who are reading this are primarily mathematicians or math enthusiasts, I should mention that Neo-Riemannian Analysis is not in fact named after the mathematician, but instead after the music theorist Hugo Riemann, whose work focused on dualism (simply put, the idea that major and minor triads are opposites) and transformations. Lewin took Riemann's transformations and abandoned dualism to apply transformational theory to music that used triadic atonality.

Neo-Riemannian Theory defines three operations:

- The R transformation: It moves the fifth up a whole step (2 half-steps) in a major triad and the root down a whole step in a minor triad.

- The L transformation: It moves the root down a half step in a major triad and the fifth up a half step in a minor triad.

- The P transformation: Exchanges a major triad for its minor counterpart, and vice versa. It's simply a shorthand for $R(LR)^3$

How is this a GIS? It's clear our space is not comprised of individual notes, but instead of triads. We'll need new notation to represent these triads. Remember the clock from earlier? We'll put that into use, and replace C with 0, C# with 1, etc. We'll call this set $a$, and can now construct our musical space by constructing the following two elements for each element $n \in a$:

- $n_{maj} = [n, n+4, n+7]$

- $n_{min} = [n, n+3, n+7]$

For example, for $n=4$, we have $n_{maj}$ and $n_{min}$ as follows:

A major chord built off of $n=4$ (left) and a minor chord built off of $n=4$ (right).

We can define these transformations:

$$L.n_{maj} = (n+4)_{min}$$

$$L.n_{min} = (n+8)_{maj}$$

$$R.n_{maj} = (n+9)_{min}$$

$$R.n_{min} = (n+3)_{maj}$$

$$P.n_{maj} = n_{min}$$

$$P.n_{min} = n_{maj}$$

Now it's easy to verify that $P = R(LR)^3$. Now that we've defined our transformations, we can verify that they form a GIS. We have an identity element: doing nothing. Proving associativity is straightforward.

To determine the groups structure, we only need to look at $L$ and $R$, as $P=R(LR)^3$. Note that:

$$ LR.n_{maj} = (n+5)_{maj} $$

$$ LR.n_{min} = (n+7)_{min} $$

This means that in order for us to get back to our original state, we must apply $LR$ 12 times, so $LR$ is of order 12. This means that we can define our group like so:

$$ G = \langle L, R, P | P=R(LR)^3, (LR)^{12}=P^2=(LRP)^2-1 \rangle $$

Our definition above shows us that our group is isomorphic to $D_{24}$.

In summary, our musical space consists of major and minor chords, which we notate as $n_{maj}$ and $n_{min}$ for any note $n$. Our group is defined above, and consists of the combination of $P$, $L$, and $R$ transformations, with the former being a combination of the latter 2. We can finish defining our GIS with a function $int: S \times S \to G$ which given chords $s, t \in S$ produces the transformation in $G$ required to go from $s$ to $t$.

The Tonnetz

Before we get to applying these transformations to a piece of music, it can help to visualize our musical space. For that we turn to the Tonnetz2. The Tonnetz provides a way to visualize our triads and the transformations in our space. Let's begin by picking a single triad, we'll use a C major triad, and finding a geometric representation. Our triad has 3 notes, so a triangle is the most obvious choice.

A 2-d representation of a C Major Chord

In addition to having 3 notes, we have 3 operations we can perform: $P$, $L$, and $R$. Additionally, since each of these operations always preserve 2 of the 3 notes, we can simply draw 3 new triangles each of which share a side with the original.

Visualizing the $P$, $L$, and $R$ operations.

We can continue to extend this diagram, and we will eventually reach a point where we have drawn all 24 major and minor triads. In fact, our Tonnetz has created a cycle both horizontally and vertically:

An extension of the previous diagram. This isn't the complete Tonnetz.

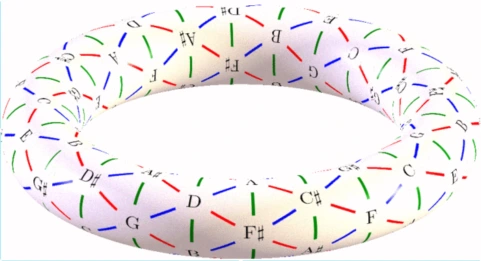

The Tonnetz is actually isomorphic to a torus, meaning we can view the entire thing in 3 dimensions.

The Full Tonnetz

Using the Tonnetz and Neo-Riemannian Analysis

Finally, we can use all the tools we've developed thus far to analyze a piece. Let's begin with an example from Radiohead: "Morning Bell". The following progression comes from the Bridge.

You can hear the progression starting here at 2:23 till 2:33.

The progression is very hard to analyze functionally, particularly because our "key" is A major, but that makes chords like the G# Minor and A minor particularly hard to explain3.

We can understand this chord progression by viewing the path on a Tonnetz:

The first 2 chords visualized on a Tonnetz

For the first two chords, we can see that they are separated by an $LP$ transformation. This $LP$ transformation is very common, and is often called a "chromatic mediant"4. Chromatic mediants are quite useful to add color to a piece, and it's harmonic motion.

We can also look at the transformation from G# minor to D major:

G#m to D on a Tonnetz

The two chords are separated by an $RPR$ transformation: more transformations means the chords are farther apart, and the resulting sound is surprising. We can see this from the sheet music as well; the triads share no common tones.

The next transformation, from D major to A major, can be explained tonally. If we're considering our "key" to be A major, then we can view this as a $IV$-$I$ progression, or a plagal cadence. This is a common way to resolve music, in addition to the $V$-$I$ we used at the beginning of this post. The last transformation is the most obvious: a parallel transformation.

Finally, "Morning Bell" also provides a convenient example for how we can transform a group of chord progressions. Let's recall the group of transformations we performed on a single note earlier. It's very easy to modify those operations to work on chords rather than notes. Instead of $T_n$ moving a note $n$ steps, it will do the following:

$$T_n.a_{maj/min} = (a+n)_{maj/min}$$

Now let's look at a similar progression from "Morning Bell", this time from the beginning of the piece.

This might seem completely different that the progression from earlier, however, we can notice the voice leading (how each individual note moves) is very similar to the voice leading in the middle 4 chords from earlier (Em-G#m-D-A). Look what happens when we apply a $T_7$ transformation to the progression:

We get the same progression!

Using a combination of $PLR$ operations and $T$ operations5 can help you uncover patterns in pieces of music. Analyzing music is helpful not only for musicians, but also for listeners. Understanding what is going on in the music you listen to, even if it's at a high level, can help you better appreciate the music.

If none of that made sense, that's fine. I'll define most of those terms much more rigorously in the next section.

Many mathematicians joke that we name everything after the second person who discovered something, because Euler discovered it first. The Tonnetz might not be named after anyone, but it was created by Euler as well.

We could also think of the piece as being in A minor, but then the G# minor and A major chords are hard to explain.

Chromatic mediants can also be found through other transformations. $PR$, $PL$, and $RP$ can also transform a chord into one of its chromatic mediants.

We didn't talk about $I$ operations (inversions) in this post, but together with $T$ operations, it forms the T/I-group, which is just as important as the PLR group. You can read about them (along with some other important information) here.